it’s time to conceptualize the “information operations kill chain.” Information attacks against democracies, whether they’re attempts to polarize political processes or to increase mistrust in social institutions, also involve a series of steps. And enumerating those steps will clarify possibilities for defense.

Tag: software

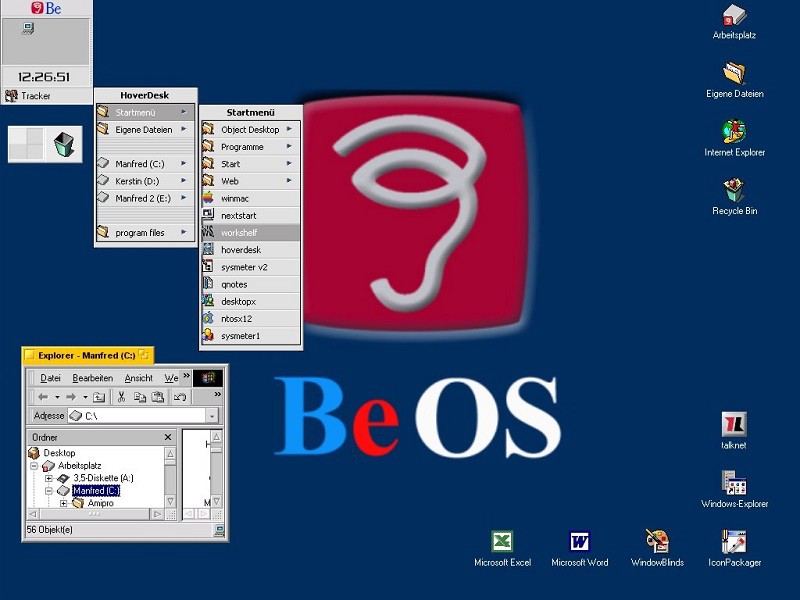

Be: Concept To Death

Be, the company Steve Sakoman and I founded after leaving Apple, had a great product idea, or so we thought, only to discover that a bad choice of partner would almost destroy the company.

Intangible Assets

The portion of the world’s economy that doesn’t fit the old model just keeps getting larger. That has major implications for everything from tax law to economic policy to which cities thrive and which cities fall behind, but in general, the rules that govern the economy haven’t kept up. This is one of the biggest trends in the global economy that isn’t getting enough attention.

If you want to understand why this matters, the brilliant new book Capitalism Without Capital by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake is about as good an explanation as I’ve seen. They start by defining intangible assets as “something you can’t touch.” It sounds obvious, but it’s an important distinction because intangible industries work differently than tangible industries. Products you can’t touch have a very different set of dynamics in terms of competition and risk and how you value the companies that make them.

Haskel and Westlake outline 4 reasons why intangible investment behaves differently:

It’s a sunk cost. If your investment doesn’t pan out, you don’t have physical assets like machinery that you can sell off to recoup some of your money.

It tends to create spillovers that can be taken advantage of by rival companies. Uber’s biggest strength is its network of drivers, but it’s not uncommon to meet an Uber driver who also picks up rides for Lyft.

It’s more scalable than a physical asset. After the initial expense of the first unit, products can be replicated ad infinitum for next to nothing.

It’s more likely to have valuable synergies with other intangible assets. Haskel and Westlake use the iPod as an example: it combined Apple’s MP3 protocol, miniaturized hard disk design, design skills, and licensing agreements with record labels.None of these traits are inherently good or bad. They’re just different from the way manufactured goods work.

more of the economy is moving to intangible assets

Information warfare attack

As DHS, DNI, FBI, and the Pentagon come together before the public to say Russia is actively attacking our midterm elections, as we have long been warned they’d do, please remember that exactly 2.5 weeks ago Donald Trump stood next to Russian President Vladimir Putin, refused to confront him on the 2016 infowar campaign our intelligence officials all say happened, and called Putin’s denial of the 2016 infowar “strong and powerful.”

Seeing all the intel chiefs on stage say one thing, and knowing the President — who wasn’t there? — believes another was weird.

All of the directors seemed to be saying they believe the nature of the attacks was overwhelmingly psyops, or online campaigns intended to influence opinion and voting choices, rather than direct attacks on voting infrastructure.

General Magic

Chances are that you’ve never heard of General Magic, but in Silicon Valley the company is the stuff of legend. Magic spun out of Apple in 1990 with much of the original Mac team on board and a bold new product idea: a handheld gadget that they called a “personal communicator.” Plugged into a telephone jack, it could handle email, dial phone numbers, and even send SMS- like instant messages—complete with emoji and stickers. It had an app store stocked with downloadable games, music, and programs that could do things like check stock prices and track your expenses. It could take photos with an (optional) camera attachment. There was even a prototype with a touch screen that could make cellular calls and wirelessly surf the then- embryonic web. In other words, General Magic pulled the technological equivalent of a working iPhone out of its proverbial hat—10 years before Apple started working on the real thing. Shortly thereafter, General Magic itself vanished.

Inaudible voice attacks

We test our attack prototype with 984 commands to Amazon Echo and 200 commands to smartphones – the attacks are launched from various distances with 130 different background noises. Attack success at 8m for Amazon Echo and 10m for smartphones at a power of 6 watt.

ParadiseOS

Paradise OS imagines an alternate version of 1999 where the personal computer is a gateway to a commercialized global network. Palm Industries, a former mall developer turned technology giant effectively controls all online experiences. Acting as a time capsule, the desktop captures the moments of December 30, 1999 — just days before a catastrophic Y2K event leads to the computer emerging in our dimension. Participants explore this frozen moment from time, using the content to discover more about the world from which it came. The project references the visual vernacular of the 20th century American shopping mall. It establishes a connection between the mall and the Internet as escapist experiences and hubs of social activity.

Computer latency 1977-2017

Compared to a modern computer that’s not the latest ipad pro, the apple 2 has significant advantages on both the input and the output, and it also has an advantage between the input and the output for all but the most carefully written code since the apple 2 doesn’t have to deal with context switches, buffers involved in handoffs between different processes, etc.

PowerPoint History

In 1987, a company called Forethought, founded by 2 ex-Apple marketing managers, rolled out PowerPoint and business meetings have never been the same since. Over at IEEE Spectrum, David C. Brock tells the story: (Robert Gaskins) envisioned the user creating slides of text and graphics in a graphical, WYSIWYG environment, then outputting them to 35-mm slides, overhead transparencies, or video displays and projectors, and also sharing them electronically through networks and electronic mail. The presentation would spring directly from the mind of the business user, without having to first transit through the corporate art department. While Gaskins’s ultimate aim for this new product, called Presenter, was to get it onto IBM PCs and their clones, he and (Dennis) Austin soon realized that the Apple Macintosh was the more promising initial target. Designs for the first version of Presenter specified a program that would allow the user to print out slides on Apple’s newly released laser printer, the LaserWriter, and photocopy the printouts onto transparencies for use with an overhead projector… In April 1987, Forethought introduced its new presentation program to the market very much as it had been conceived, but with a different name. Presenter was now PowerPoint 1.0—there are conflicting accounts of the name change—and it was a proverbial overnight success with Macintosh users. In the first month, Forethought booked $1M in sales of PowerPoint, at a net profit of $400K, which was about what the company had spent developing it. And just over 3 months after PowerPoint’s introduction, Microsoft purchased Forethought outright for $14M in cash.

Skeuomorphic hell

Alone, each plugin is hideous in its own unique way. A panel of 3D knobs here, a pixelated oscilloscope there. But when a project really gets cooking, one can amass 8 or 10 of these interfaces overlapping each other on the screen at once, and that’s when skeuomorph hell really comes into focus. I don’t know why audio software has looked like this for the better part of 20 years, but I’d like to honor these sins of UI with a tour of some of the most egregious examples.