The researchers let the cell clusters assemble in the right proportions and then used micro-manipulation tools to move or eliminate cells — essentially poking and carving them into shapes like those recommended by the algorithm. The resulting cell clusters showed the predicted ability to move over a surface in a nonrandom way.

The team dubbed these structures xenobots. While the prefix was derived from the Latin name of the African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis) that supplied the cells, it also seemed fitting because of its relation to xenos, the ancient Greek for “strange.” These were indeed strange living robots: tiny masterpieces of cell craft fashioned by human design. And they hinted at how cells might be persuaded to develop new collective goals and assume shapes totally unlike those that normally develop from an embryo.

2021-11-29: And now they reproduce

The same team that built the first living robots (“Xenobots,” assembled from frog cells — reported in 2020) has discovered that these computer-designed and hand-assembled organisms can swim out into their tiny dish, find single cells, gather 100s of them together, and assemble “baby” Xenobots inside their Pac-Man-shaped “mouth” — that, a few days later, become new Xenobots that look and move just like themselves. And then these new Xenobots can go out, find cells, and build copies of themselves. Again and again. “These are frog cells replicating in a way that is very different from how frogs do it. No animal or plant known to science replicates in this way. We’ve found Xenobots that kinematically replicate. What else is out there?”

2023-07-04: Interview with Michael Levin about the amazing latent abilities of cells. This seems to be true recursively.

A big theme of your work has been that organisms have latent abilities—that the behavior we see in nature is contextual and that, by altering the circumstances, you coax them to do totally different things. What are some examples?

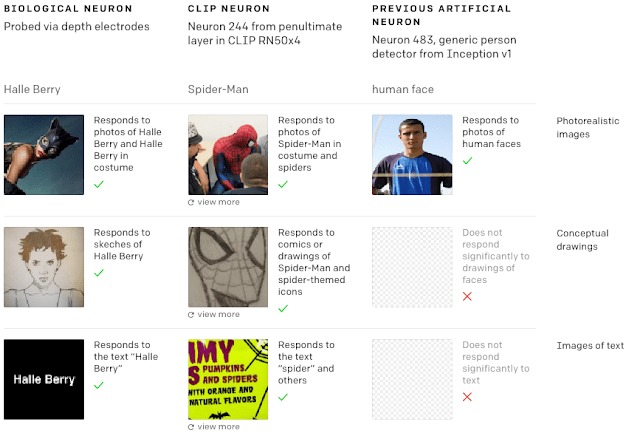

We are lulled into thinking that frog eggs always make frogs, and acorns always make oak trees. But the reality is that once you start messing around with their bioelectrical software, we can make tadpoles that look like other species of frogs. We can make planaria that look like other species of flatworms across 150 million years of evolutionary distance—no genetic change needed, same exact hardware. The same hardware can have multiple different software modes.

You can look at frog skin cells and say, “All they know how to do is how to be this protective layer around the outside. What else would they know how to do?” But it turns out that if you just remove the other cells that are forcing them to do that, you find out what they really want to do—which is to make a xenobot and have this really exciting life zipping around and doing kinematic self-replication. They have all these capacities that you don’t normally see. There’s so much there that we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of.

Some object to speaking of what the cells “know” or “want” to do. Do you think that a concern about being anthropomorphic or anthropocentric has hindered research in this?

Incredibly so. I love to make up the words for this stuff because I think they need to exist—“teleophobia.’’ People go screaming when you say, “Well, it wants to do this.” People are very binary because they’re still carrying this pre-scientific holdover. Back in before-science times, you could be smart like humans and angels, or you could be dumb like everything else. That was fair enough for our first pass in 1700, but now we can do better. You don’t need to be at either of these endpoints. You could be somewhere in the middle. When I say this thing “wants to do XYZ,” I’m not saying it can write poetry about its dreams. It doesn’t necessarily have that kind of second-order metacognition; it doesn’t know what it wants. But it still wants.

Are the cells of our body continually measuring the payoff of cooperating vs. defecting, too?

Yes, but if you are a cell that’s connected strongly to its neighbors, you are not able to have these kinds of computations. “Well, what if I go off on my own? I could just leave this tissue. I could go somewhere else where life is better. I could set up my own little tumor.” You can’t have those thoughts because you are so tightly wired into the rest of the network. You can’t say, “Well, I’m going to ….” There is no I; there’s we. You can only have those thoughts, “What am I going to get?” when you’re not part of the group.

But as soon as there’s carcinogen exposure or maybe an oncogene that gets expressed, the electrical connection starts to weaken. It’s a feedback loop, because the more you have those thoughts, the more you’re like, “Well, maybe let me just turn that connection down a little bit. Now I’m really coming into my own. Now I’m out of here. I’m metastasizing.”

So a carcinogen would work in this case by disrupting the bioelectrical connections.

Exactly. What we’ve done in the frog system, and we’re now moving into human cells, is to show that [electrical weakening] happens, and that you can prevent it and prevent normalized tumors by artificially forcing the electrical connection. We can shoot up a frog with strong human oncogenes and then show that, even though those are blazingly strongly expressed, there’s no tumor because you’ve intervened. You’ve forced the cells to be in electrical communication despite what the oncogene is trying to get it to do.

2024-01-22: Basal cognition

Regular cells—not just highly specialized brain cells such as neurons—have the ability to store information and act on it. Now Levin has shown that the cells do so by using subtle changes in electric fields as a type of memory. These revelations have put the biologist at the vanguard of a new field called basal cognition. Researchers in this burgeoning area have spotted hallmarks of intelligence—learning, memory, problem-solving—outside brains as well as within them. Basal cognition offers an escape from the trap of assuming that future intelligences must mimic the brain-centric human model. For medical specialists, there are tantalizing hints of ways to awaken cells’ innate powers of healing and regeneration. “What we are is intelligent machines made of intelligent machines made of intelligent machines all the way down.”